Kairangahau profile: Oriwa Tamahou

Oriwa, a technician in our Māori Partnerships team, facilitates meetings with a community of researchers at AgResearch, according to the maramataka (Māori lunar calendar) to share knowledge of tikanga and te ao Māori. Oriwa also contributes to soil revitalisation trials and help farmers understand and incorporate Mātauranga Māori to heal damaged whenua.

Oriwa was born and raised in Rotorua, where she attended Rotorua Girls’ High School. Her tūrangawaewae (place to stand and call home) is Maungapōhatu, Ruataahuna, and Te Urewera.

“My parents took us home as often as they could,” for weddings, birthdays, hapū hui, marae working bees, and tangi (funerals).

“We would have our six-week summer holidays back in Maungapōhatu which had no power, no running water, and definitely no cell reception or wifi. But those were the best times I can recall…we always had what we needed; kai, manaaki, love, and lots of whānau around us.”

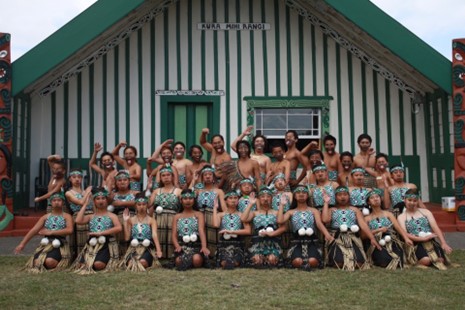

Whānau noho on Oriwa’s pāpā side, taken outside Tanenuiarangi at Te Mapou marae at Maungapōhatu

Oriwa remembers catching the semi-wild horses or using quad bikes to go hunting and swimming, and building huts with whatever natural resources they could find.

“Mum and Dad never worried about us back there, they only told us, ‘Don’t get hurt, it’s a three-hour drive to the nearest hospital’, everything else was fair game.

“I’ve always loved science, so actually, in 2017, my last year of high school, I was actually looking at doing Zoology.”

The initial plan Oriwa had, had changed when her 13-year-old niece took her own life in January of that year.

“That kind of inspired, it hit a nerve in me to seek out tools developed to help people.”

Oriwa realised she wanted to focus more on people: “helping people get out of that space, and not let it get that bad, especially with Māori. That was my drive for social science.”

She has since graduated from Waikato University with a Bachelor of Social Sciences. Oriwa is currently completing her master’s degree at Te Whare Wānanga o Awanuiarangi. She describes social science as “a lot of reading, researching and getting to know who you’re working with.”

Oriwa then applied for close to 50 internships, both nationally and internationally, and AgResearch was one that got back to her straight away.

Before her interview for a place in Te Puāwaitanga (AgResearch’s Māori internship programme), Oriwa did some background research, and found plenty of science information, but very little evidence of AgResearch’s work within te ao Māori.

Oriwa got in touch with Louise Hennessy (Te Puāwaitanga programme coordinator) to withdraw her application. “As a Māori social science major, I didn’t see myself within the organisation and I just didn’t want to waste anyone’s time.

“She [Louise] got back to me, and now we laugh about it because we’re mates. Basically she told me her backstory around how she started on the internship and she’s been here for 10 years, and just to try it out.”

Oriwa took Louise’s advice and hasn’t looked back.

The internship project, which Oriwa had shaped and structured with a Kaupapa Māori approach, involved interviewing AgResearch’s current or past Māori partners, to understand their perspective on the working relationship. She found herself becoming more and more relevant within the organisation, finding that AgResearch had been on and continue to be on a journey to committing to their role as treaty partners alongside Māori.

“From that, I produced the report and that gave some recommendations for AgResearch staff to use internally, to help them in this space with working with Māori.”

One of her key findings was that from a Māori perspective, the whanaungatanga (relationship building) stage of a project is often rushed. Western project timelines rarely allow for the time it takes to build valuable relationships, with longevity.

“The building and maintaining of relationships are the most important thing to consider when working with partners, whether Māori or not. The relationships you hold can lead to further, future endeavours.

"It is obvious when a researcher has built a strong relationship with Māori because they may be invited to other events run by these partners. It is in these settings that Māori may be willing to share Mātauranga Māori that is typically held close to the chest".

Mataatua rangatahi team of 2013, Oriwa is on the far left in the second row.

After her internship in the summer of 2022, she was offered a full-time role in the Māori Research and Partnerships Team.

She is currently working on several projects, including Revitalise Te Taiao, a programme within the Our Land and Water National Science Challenge; a biosecurity project led by Māori which looks to empower hapū to be aware of potential biothreats and how to respond, according to hapū visions; the Māori research strategic plan within AgResearch; and the T-Platform, which is an internal group that supports transformative and transdisciplinary approaches adopted by our researchers.

One of the recommendations from her internship report was the need to set up an internal community within AgResearch so researchers can share experiences of working with Māori partners. As a result, she now runs a Community of Practice (CoP), which has grown to include over 80 researchers and scientists (called Ngā Manu Kai Miro).

Oriwa uses whakataukī to explain the kōrerorero (meaning) of the CoP name.

Ko te manu e kai ana i te Miro, nōna te ngahere. Ko te manu e kai ana i te mātauranga, nōna te ao – The bird who feasts on the Miro berry, theirs is the forest. The bird who feasts on knowledge, theirs is the world.

CoP runs according to the maramataka, meaning that in certain moon phases it may not be an appropriate time to gather or to discuss particular topics. Each gathering observes tikanga; beginning with mihi and starting and ending with karakia.

“I run the sessions by the different maramataka, the different moon phases, and I encourage the group to go out and find their own resources from the regions they reside in. There’s been a couple guest speakers, both external and internal speakers. And they’re usually non-Māori scientists or researchers who share what went well, what didn’t go so well, and what they learned from the different Māori entities that they’re working with.”

The kōrerorero has personal significance for Oriwa too.

After she attended a hui in her papakāinga (iwi-affiliated homelands) Ruataahuna, she gained a deeper appreciation of how her elders were special experts of their ngahere.

They attended a school system that deterred them from learning from their whānau/hapū. This was an unwelcome by-product of learning through the lens of western educational systems.

Despite this, Oriwa's elders helped her acquire knowledge that they had learnt, not through books, but through their own observations and Mātauranga tuku iho (passed down knowledge).

"One of the main purposes of the CoP is to build capability around how we work within environments that tangata whenua hold close to their hearts."

But to improve interactions with Māori, she says, we must listen to the manu in the ngahere.

Oriwa explains further, using whakataukī:

Ngā Manu Kai Miro - we must understand the manu that partakes on the Miro berry, in order to understand the deep-seated connection they have to their whenua.

Another project Oriwa is involved in is Revitalise Te Taiao, which aims to use both Mātauranga Māori and Western science to inform environmental restoration. There are three pilot trials in Taranaki, Wānaka and Paeroa.

AgriSea, who are based in Paeroa, lead one of the pilots, called Rere ki Uta, Rere ki Tai. The trial involves ten dairy farms: five Māori-owned and five non-Māori owned. Farmers are experimenting with a natural seaweed fertiliser, AgriSea, to enhance the mana and mauri of the soil.

“They’re looking at 10 different dairy farms within the Waikato-Bay of Plenty area, and looking to see if we put Mātauranga Māori at the forefront of everyone’s minds, enhancing the mana and mauri of soil, how does that inform farmers’ next steps?”

Oriwa with her cousin, Dr Rangi Mataamua, at a Maramataka wānanga he held in Ruataahuna

By viewing the soil as more than a “holding place” in which crops grow, the farmers are using Mātauranga Māori to improve the health and therefore, the profitability of their land.

WAI Wānaka is a community-based pilot, involving a group who are passionate about restoring their rivers and lakes. They are hoping to work alongside Kai Tahu Rūnaka and the mana whenua to support them in restoring te Taiao (the environment).

Te Kahui Rau is the third pilot within Revitalise Te Taiao, led by Ngāti Tāwhirikura (Taranaki-based hapū). This rōpū (group) is looking at how land-use management can help to heal their people after historical land confiscation, especially through māra kai (growing food).

Oriwa has an important and busy job.

She uses another whakataukī to describe the task ahead:

Nāu te rourou, nāku te rourou, ka ora ai te iwi - with your food basket and my food basket, the people will thrive.

It describes the importance of community, teamwork, and a strengths-based strategy.

"It also recognises that everyone has something to contribute, a piece of the jigsaw, and that by cooperating, we can all succeed. It symbolises what I will set out to achieve."